” ‘Will I come?’ he said at once. ‘There’s no need to ask. Of course I’ll come. You’ve only got to say gold and I’m your man.'” (p 71)

My Top 10:

- Treasure of the Sierra Madre

- Hamlet

- Force of Evil

- Fanny

- Day of Wrath

- Rope

- The Eagle Has Two Heads

- State of the Union

- Cesar

- The Snake Pit

Note: I actually have a lot more than 10 on my list in this year. There are 19 films on my complete list. Four of the remaining films on my list are reviewed below because they were WGA nominated: my #11 (All My Sons), #14 (Key Largo), #15 (Call Northside 777) and #18 (Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House). The rest are in list order at the very bottom.

Consensus Nominees:

- Treasure of the Sierra Madre (264 pts)

- The Snake Pit (200 pts)

- I Remember Mama (120 pts)

- Sitting Pretty (80 pts)

- Johnny Belinda (80 pts)

Oscar Nominees (Best Screenplay):

- Treasure of the Sierra Madre

- Johnny Belinda

- The Snake Pit

note: The other nominees, A Foreign Affair and The Search, qualify as original screenplays.

Oscar Nominee (Best Original Story):

- The Red Shoes

note: Yes, it was nominated for Best Original Story, but today it would qualify as Adapted, so I’m including it.

WGA Awards:

Note: Because the categories at the WGA were divided by genre rather than by source, there are numerous films that were nominated but are not relevant to this post.

Drama:

- The Snake Pit

- All My Sons

- Another Part of the Forest

- Call Northside 777

- Command Decision

- I Remember Mama

- Johnny Belinda

- Key Largo

- Sorry Wrong Number

- Treasure of the Sierra Madre

Nominees that are Original: Berlin Express, Naked City

Comedy:

- Sitting Pretty

- Apartment for Peggy

- I Remember Mama

- June Bride

- Miss Tatlock’s Millions

- Mr Blandings Builds His Dream House

Nominees That Are Original: A Foreign Affair, The Mating of Millie, No Minor Vices, The Paleface

Musical:

- That Lady in Ermine

- When My Baby Smiles at Me

Nominees That are Original: Easter Parade, The Emperor Waltz, Luxury Liner, On an Island With You, You Were Meant for Me

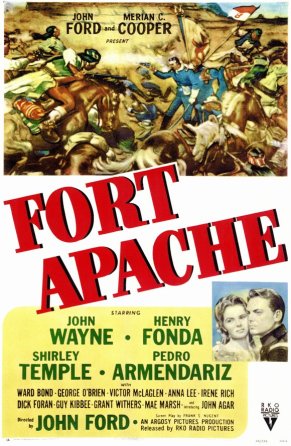

Western:

- Treasure of the Sierra Madre

- Fort Apache

- Four Faces West

- Fury at Furnace Creek

- Green Grass of Wyoming

- Rachel and the Stranger

- Red River

- Station West

Nominees That are Original: Man from Colorado, The Paleface

Screenplay Dealing Most Ably with the Problems of the American Scene:

- The Snake Pit

- All My Sons

- Another Part of the Forest

- Apartment for Peggy

- Call Northside 777

- Command Decision

- Cry of the City

- I Remember Mama

Nominees that are Original: Louisiana Story, Naked City, Street With No Name

The Treasure of the Sierra Madre

I have already reviewed this film once. It is a film that has continued to rise in my estimation ever since I first saw it (on a television where I turned the colorization off by adjusting the color knob – stupid Ted Turner). It is one of the great films of all-time containing what might be the best performance from one of Hollywood’s greatest actors.

The Treasure of the Sierra Madre by B. Traven (1934)

I admit, I would not have seen in this novel what John Huston so clearly saw – the potential for a film that would be one of the all-time greats. It is a good enough novel – the story of one man who ends up beaten down so much that he can not trust himself. When he finally has the chance to make himself rich, even though it is at the cost of the men he has been working side by side with, he takes it. Little does he know what it will cost him.

It is interesting that this wasn’t written by an American. The story of a man in the west (actually, down in Mexico, but it serves the same kind of function) who succumbs to greed, only to have it serve as his final downfall, sounds like something that would come out of an American writer. But Traven, a mystery man, wrote this is German.

But what was in here was clearly a blueprint for a great film. Most of the film is right there on the page, from those opening moments of desperation (“I never knew you were the same person. I never looked at your face till this moment.”) to the days up on their stake (“So it went on day after day without a break. Their backs were so stiff they could neither stand nor lie nor sit. They hands were like horny claws. They could not bend their fingers properly.”), to the desperate end of Dobbs (“With a practised hand he drew it in one sweep from its long leather sheath; the next moment he was above Dobbs, whose head with one short sharp blow he struck clean from his neck.”). It is a solid novel, from start to finish.

All of this may seem strange if you look at what I wrote in my Nighthawk Awards for 1948, but I couldn’t get into the novel the first time I read it, some 15 years ago, and this time I was able to flow into more easily and so my estimation of it has gone up.

All quotes from the Basil Creighton translation.

The Adaptation:

If you are at all interested in how this screenplay came about, there are two invaluable sources to go to. The first, of course, is the published screenplay. It is the most recent film to be published in the Wisconsin / Warner Bros series. It is a valuable book, not just as a script, but also because of the introduction which discusses the process of putting together the film, as well as the footnotes which detail various scenes that were either altered or cut and thus differ between the published screenplay and the final version of the film that was released.

The second source is one of the best books ever put out about film, Inside Warner Bros (1935-1951), edited by Rudy Behlmer. The memos in the Warners Archives cover 20 pages in this book and a period of over seven years. The first is from November 14, 1941 about the availability of the book and the difficulty in acquiring the rights. Even that early, John Huston wanted to make it into a film. At least one draft of the script was complete by the summer of 1946, because B. Traven read it and responded to John Huston on September 2. Traven’s letter is several pages and makes a few suggestions while also commending Huston for the quality of the script. Huston responded to each of the individual points and worked some of them into the final film.

Overall, much of the film comes directly from the book. Even parts I had completely forgotten (the opening scene where Dobbs keeps hitting up the same man in the white suit for money) come almost verbatim from the book. There are some changes of course. One is rather important, even if it doesn’t seem so. In the book, the man is only named Dobbs. But in the film, he is really attached to his full name, and so the name Fred C. Dobbs became a part of the American film lexicon.

The Credits:

Directed by John Huston. Screen Play by John Huston. Based on the Novel by B. Traven.

Hamlet

I have already reviewed this film once, when writing about Olivier as a Top 100 Director. I also wrote about this film in the Best Picture post when I discussed it in relation to other film versions of Hamlet. That paper was an excerpt from a paper I wrote in grad school, and there is more about that below. It is the second great Shakespeare film, following Olivier’s Henry V. In fact, until Branagh, there was hardly a great Shakespeare film that didn’t have Olivier in it.

Hamlet by William Shakespeare

I have written before about my “perfect” works of written art. There are two poems on my list, one short story and two novels. Those five things have never changed. But later I decided that Hamlet needed to be on there as well. There was a time when I thought Macbeth the greater play and I have a fondness for A Midsummer Night’s Dream that will never fade a bit, but this is the greatest of Shakespeare’s works.

It is such a great play because Hamlet himself is such a great character. He lives, he breathes, he brings life to the stage. One of the few times I have ever really had a chance to act was in a Shakespeare class and a classmate and I did the “nunnery” scene. We began towards the end of the “To be or not to be” soliloquy. I was holding a gun up to my temple, slowly lowered it and began with “Thus conscience does make cowards of us all.” I put the gun away as I said my final lines and then my friend Ali approached as Ophelia. After we had our interplay, she handed my the letters and began to walk away. “Are you honest?” I asked and as she turned, the gun comes up, aiming at her.

Our teacher hated it. It went against what she believed in when it came to Hamlet. I defended it. I still defend it. That’s one of the glories of Hamlet – there is so much in the play, with such rich language, that you can do so many things with it. I had classmates in college who did it and they did it with a Nazi invasion theme. It’s a play I never tire of reading and never tire of seeing. As I write this, I am a few hours away from seeing Benedict Cumberbatch through the National Theatre live perform in it.

One thing in particular that didn’t strike me, either the first time I read it for a class (high school), or the next two times (Brandeis, Pacific). It hit me before I studied it at Arizona State and it was a vital part of the play for me by the time I wrote the paper on it at Portland State. It contains a few of my favorite lines of any Shakespeare play and they are ones that are often overlooked, ones that are actually in prose, not verse. They struck me so much in watching In the Bleak Midwinter, one of the best Hamlet films, which isn’t even really Hamlet. It is those fateful words that Hamlet says to Horatio before the final due, the ones that really echo in my mind even more than “to be or not to be” and seem to sum up Hamlet in its entirety in just a few beautiful words:

“There is special providence in the fall of a sparrow. If it be not now, ’tis not to come; if it be not to come, it will be now; if it be not now, yet it will come. The readiness is all.”

The Adaptation:

As mentioned above, I have already written much about this film version and what it does with the play. It cuts much of the play, eliminating Fortinbras (easy) as well as Rosencrantz and Guildenstern (more difficult, and eliminates some of the humor). It also really pares down the speeches, especially any longer speech spoken by anyone other than Hamlet.

But aside from the cuts, perhaps what this film does, more than any other film version, is choose a particular interpretation, and it does it openly. Before the film really begins we hear Olivier’s voiceover: “This is the tragedy of a man who could not make up his mind.” That is certainly a valid interpretation of the play and one that Olivier sticks too (he also presents the Freudian interpretation somewhat with the closet scene, but not nearly as much so as some later versions do).

Rather than reiterate so much of what I have written before, and rather than even offer up an excerpt again, like I did the first time, instead I will offer The history of Hamlet on film, which is my paper in full. Enjoy, if you care.

The Credits:

Directed by Laurence Olivier. The only writing credit is “Laurence Olivier presents Hamlet by William Shakespeare” as the title.

Force of Evil

I have reviewed this film once already, if you look way down this post at the Top 5 films. It’s a great film and one that is too often over-looked, for a long time even by me.

Tucker’s People by Ira Wolfert (1943)

Ira Wolfert began as a journalist and only later branched out into fiction. In some ways, he didn’t branch out very far. This novel, his first, was inspired by a trial he covered dealing with the numbers racket in New York City. Not only that, but this reads like a novel written by a journalist. It tells a good, detailed story, it knows how to delve into the tangle of what is going on, how to make you understand it, how to bring a human element to horrible confusion and even more horrible actions.

Even better than that, it tells a moral story without moralizing. It brings you the sympathetic story of a man who is doing what he considers an honest job, even though he knows that what he does takes away money from hard-working people and funds an activity which is, at best, dubious. But it makes you understand the man, makes you understand how he got where he was, why he feels he no longer has any place else to go, and what his final fate is. And yet, it also makes you understand how he fits into a larger story and how, no matter what he does, he is far and away the most noble person we meet in the course of this story.

The Adaptation:

Tucker’s People is a 496 page novel, yet Force of Evil is only a 78 minute film. Yet, the film somehow manages to encompass most of the scope of the novel and even a lot of individual moments (I could hear Thomas Gomez screaming “What have you done to me!” as I was reading it). So, how did Polonsky and Wolfert manage to do this? Well, in a couple of ways, both of which are good examples of how to adapt a book to the screen.

The first is in dropping most of the outlying bits of the story. The entire early part of the story, dealing with the early hard times that Leo has is dropped from the film entirely, and we simply start in with Joe about to begin the process of betraying his brother. Anything that doesn’t focus almost exclusively on that plot point – the relationship between Joe and Leo and what each does in the course of that relationship over this story is dropped.

The second thing it does is eliminate a major character. But it doesn’t just drop the character entirely. It takes the relationship that this character (Wheelock) is in with a female who has been wrapped up on the edges of this business and hands it over to Joe, the younger brother and the instigator of all the trouble of the film. Therefore, we get to keep a lot of the good moments in the relationship while excising a considerable portion of the book.

All in all, much of the book is changed – by taking the female character and inserting her into the brothers’ relationship, it alters the way they interact and eventually Joe is able to find at least some measure of redemption that I wouldn’t really say he finds in the book. But it holds true to the spirit of the book.

The Credits:

Directed by Abraham Polonsky. Screenplay by Abraham Polonsky and Ira Wolfert. Based upon the novel “Tucker’s People” by Ira Wolfert.

Fanny

I have reviewed this film once already, as my under-appreciated film of 1948, even though it was originally released in France in 1932. That perhaps might be part of the point. Marius, the first film, made in 1931, was released in the States in 1933. But Fanny (1932) and Cesar (1936) wouldn’t come across the water until three years after the war had ended. What took them so long? This the best film of what has long been one of film history’s most under-appreciated trilogies.

The Source:

Fanny by Marcel Pagnol (1932)

When I wrote my Best Adapted Screenplay post for 1932-33, I mentioned that I tried twice to get an English translation of Marius, the first play in Pagnol’s wonderful trilogy, but ended up with a French copy both times. This time I was able to get a copy of the play in English, but only because someone named Jay W. Lees, who would eventually become extremely important to the theater department at Westminster College, translated the first two plays of the trilogy for his MFA thesis at the University of Utah.

This is a very solid play. If it’s not a great play, it’s because it keeps too much of the action confined, with only four scenes covering the entire length of the play. But it has two wonderful roles – those of Cesar and Fanny – and provides wit and real moving emotional moments between the characters.

I’ll let Lees himself sum up from the final paragraph of his introduction, where he explains what changes he has made (see below): “The intimacy, intensity and simplicity of the plot with its philosophical undercurrent have not been affected in order to maintain a theme abounding in affecting as well as tragi-comic and simply comic situations revolving around a gallery of human and amusing character portraits and common situations.”

The Adaptation:

Time takes place between the plays Marius and Fanny but not between the films. In the opening scene of Fanny, Marius has been gone for a while and that first scene deals with various people talking about how Cesar has been dealing with the absence of his son. But Pagnol, adapting his own play, wrote in a new opening scene that takes place immediately upon the departure of Marius so we can witness the reaction to his departure – indeed we’re a good 15 minutes into the film before we ever get to that opening scene of the play.

Although, I can’t be 100% certain of that. The translation I am reading has actually been trimmed, for the purpose of it was not to do a word-by-word translation, but to actually make English versions of the two plays that would be worthy of putting on the stage.

Aside from that, Pagnol seemed determined to make the film less stagey than the play. He was not bound by the constraints of the stage – indeed, he had all of Marseille to work with and beautiful use was made of it. The play consist of only four scenes – one in the Cesar’s bar, one in the kitchen of Fanny’s mother, one on Panisse’s ship and one in the dining room of his home. The film is very much alive, and not only does it hold to the original structure, but much of the dialogue is changed as well. Much is added to keep away from the notion of people just standing around talking to each other.

The Credits:

Directed de Roger Richebé . Réalisation de Marc Allegret.

The only mention of the original source in the opening credits is “Marcel Pagnol présente” before the title. But the only end credit is “Ce film est basé sur la pièce de Marcel Pagnol.”

Day of Wrath

(Vredens Dag)

Who would have guessed watching Vampyr, what a bleak (and small) road the rest of Carl Theodor Dreyer’s oeuvre would turn out to be. That isn’t to say that they’re not very good. They just don’t make for very fun watching. Vampyr was fascinating in its use of horror but the remaining three films, made all about a decade apart and heavy with the weight of religious guilt. After the financial (and contemporary critical) failure of Vampyr, Dreyer went into journalism before he finally got this film made in 1943. Though he denied that it was an allegory for the Nazis, he did wisely leave Denmark after the film was released to finish the war out in Sweden.

Day of Wrath moves slowly, as Dreyer’s films often do. But this is not a story that should move quickly. Dreyer himself said that he did not direct or edit the film to move slowly but that the characters themselves move slowly, as it heightens the tension. There is certainly enough tension. The film opens on a mis-matched couple (a husband about 60, a wife about 25) who are, if not happy, at least in a state of tranquility. But two things intervene to shatter that calm – the accusation of witchcraft that is moving through the town and will soon strike close to home, and the return of his 20 year old son, Martin, after several years away (including the entire period of the marriage). It does not take much imagination to know that the wife and the son will fall in love, but it is the greater story in the culture around them that will be the real downfall of happiness, for Anne, the young wife, will soon learn that her friend is accused of witchcraft and that her mother should have been burned at the stake for being a witch but was saved by her husband so that he could marry Anne. But all of this will end badly in ways we might not have expected, with Anne wishing for her husband’s death, him actually dying and then having Martin throw her aside when he genuinely believes (partially because of the influence of his grandmother who dislikes Anne) that Anne really has acted with witchcraft to kill his father.

Dreyer was a talented director, but after the sound era arrived he struggled to get films made. It would be in later years, after Criterion would start releasing his films, that he would really start to get serious critical attention and be widely regarded as a master. I think this is one of his best films, much better than The Trial of Joan of Arc, partially because of the more moving human story and partially because this time Dreyer doesn’t feel the need to pummel my visual senses with numerous over-bearing close-ups. It was a critical disappointment at the time and it would be yet another decade before Dreyer would make another film, but in a year as weak as 1948, it stands out as one of the very best films.

I wrote all that before realizing I had already reviewed the film, which you can find here.

Anne Pedersdotter by Hans Wiers-Jenssen (1908)

The easiest thing to say, of course, is that this is The Crucible for Norway (written long before Miller’s play, of course). It is derived from true events concerning Anne Pedersdotter, a woman whose death at the stake in 1590 was well-documented. Many of the real events are changed for this play (Anne was a much older woman when she was burned and had been accused once before, years earlier), but the play simply uses a real person who was burned as an example of the extremities of the era. This play, produced first in Norway in 1908, was popular enough that it was translated into English in 1917 by John Masefield, who would later by England’s Poet Laureate.

But, one of the ways in which this film is very different from The Crucible is in its approach to its material. The Crucible is designed to implicate an entire society with the folly of its decisions. But this play focuses more on one individual and the choices that he made, right or wrong, and the implications it has for his life and his soul. One of the more interesting overlaps is that both have primary male characters who are eventually doomed because of an earlier decision made out of lust.

I can not imagine that this would ever be revived, at least in America. There are too many similarities between this and The Crucible and people are more likely to take to the play which speaks to their history than one which is too easy to dismiss as a culture very different from our own.

The Adaptation:

Wikipedia notes that the film differs slightly from the play, noting that the first encounter between Anne and Martin is more sexualized in the film. That part is true, but it vastly understates the differences between the film and the play. Yes, that is a key difference, though we don’t know how a stage director would have directed that scene – it is more in the actors and the direction than in the script. But there are other notable differences aside from just that.

In the play, Anne first learns of her mother only after Herlofs-Marte has been executed and then, in a conversation with her husband with Martin listening in. In the film, Anne has already learned of it from Herlofs-Marte herself and the conversation is followed immediately upon by the start of the love affair between Anne and Martin, while in the play several scenes take place in between, and Martin only falls for her after he witnesses the brutality with which she is being viewed.

The film makes much more use of the youth of the characters – in the scene where we first meet Martin he hides himself from his father so that he can surprise him, while on stage Absalon walks in while Martin and Anne are talking.

Much of the dialogue is different between the play and the film, but in that I am reading a translated play and watching subtitles on the film, there’s no guarantee that the film doesn’t veer closer to the original text of the play.

The Credits:

There are no credits for the film. It is directed by Carl Theodor Dreyer. The IMDb credits Carl Theodor Dreyer, Poul Knudsen and Mogens Skot-Hansen for the writing. The original play is also uncredited.

Rope

Last year was the year with two films that could have been seen as gimmick films. The first, Birdman, was anything but a gimmick, and what it did magnificently worked into the film as a whole. The second, Boyhood, I absolutely thought was going to be a gimmick film, but turned out to be a thoughtful, well-made film whose ultimate banality was not because of its gimmick but because of its premise. I mention this because Rope was the film that originally did what Birdman did – make a film of all one shot. Back in 1948, cameras could only hold 10 minutes worth of film, so every ten minutes, we pan across something dark and that’s where the film was changed. The problem is that this really is a gimmick – the pan shots never feel natural and the continual shot just reminds us that this was originally a play that all took place in one location. It is the least Hitchcock of any Hitchcock films, yet, in some ways, is still very much a Hitchcock film, and that’s really all about the tension.

Rope is a bit of a philosophical film. It’s the story of two young men who believe that they are superior beings, that they have the right to commit murder of someone they deem inferior. We know they have done this because we see it in the first scene of the film – them strangling their supposed friend and placing his body in a chest which will then be covered with candles for a party they are about to host, which includes his parents, in a rather grotesque display of their so-called superiority.

All of this might not have worked very well if not for the casting of Jimmy Stewart as a man who was their counsellor at prep school and has also been invited to the party. It was his notions of superiority, much more at the metaphysical level, that gave them their own ideas and they want to be able to trumpet their fearlessness in going through with his ideas, something they feel he was always too nervous to do himself.

If that sounds all a bit Dostoevskian, it is saved from being overly philosophical (but not overly talky) by the tension in the error. We know the body is in the case. They know the body is in the case. The tension comes from the possibility of discovery of that body. This is 1948, and unless you have Clarence Darrow defending you like Leopold and Loeb (the supposed inspiration for the story, but see below), you are going to hang for murder. And Stewart, back from the war and finding a new level of complexity in his characters, makes every word he speaks count, whether he is lording his own superiority over people or reminding someone in the end, the value of another human life.

Rope is not a great film, and even having it at the low-level end of ***.5, I have probably rated it higher than many people would. But that’s because, aside from Hitchcock’s ability to ramp up the tension, I am intrigued by the arguments over it all. I do wish it had better performances (Farley Granger is decent as the more tortured of the pair, but John Dall’s smug superiority makes pretty much everyone in the film and the viewers want to punch him) and I wish Hitchcock hadn’t gone with the gimmick. But it’s an intriguing film, and just because it doesn’t have the visual flair of great Hitchcock, doesn’t mean it should be ignored either.

Rope: A Play by Patrick Hamilton (1929)

As is widely known, of course, Rope is derived from the Leopold and Loeb case, in which two young wealthy men killed a boy to prove their superiority. The author, Patrick Hamilton, disputes this however, in an preface to the published version of the play in 1929: “It has been said that I have founded ‘Rope’ on a murder which was committed in America some years ago. But this is not so, since I cannot recall this crime having ever properly reached my consciousness until after ‘Rope’ was written and people began to tell me of it. But then I am not interested in crime.”

The play is an interesting meditation on whether anyone has the right to kill someone else. But that’s secondary to the suspense of the play. Hamilton intended to downplay any philosophical notions and made it more about the suspense, as he also notes in the introduction: “I certainly hope, of course, that ‘Rope’ is an unusual and original kind of thriller – and this is in that it endeavours to obtain its thrills without the employment of what has always been to me disgusting in the true sense of the word – namely, physical and visual torture upon the stage.” And it is an intriguing thriller – though we don’t see the murder and the victim shoved into the case (it would have been more difficult to have that poor person there the whole play), we know fairly early on what they have done and the potential for discovery.

The Adaptation:

The plot for Rope comes directly from the play (Arthur Laurents in the book The Hollywood Screenwriters answers whether he considers himself the author of Rope says “Even though the dialogue was totally mine, the material came from a play; and the picture followed the structure of the play (too closely, I thought)”) – two men murder a “friend” of theirs due to the feelings of moral superiority, then give a party with the body basically sitting right in front of everyone without them knowing it. At the end, the main conspirator, Brandon, is almost desperate to let someone know that he has done this, that someone being Rupert (in the original play he’s a friend and poet, but in the film he’s the former housemaster to the two murderers). But, aside from the basic premise of the play, almost everything is different. The relationship is different, the characters are different (other than having the parents of the victim there) and almost every line of dialogue except for a few at the very end of the film is completely different. If it’s been a long time since you’ve seen the film and you were to read the play, you might remember them being the same because the structure and plot is the same, but if you were to read it and watch the film close together, it’s easy to see how very different they are.

The Credits:

Directed by Alfred Hitchcock. Adapted by Hume Cronyn from the Play by Patrick Hamilton. Screenplay by Arthur Laurents. The IMDb lists uncredited writing from Ben Hecht.

The Eagle Has Two Heads

(L’Aigle A Deux Tetes)

Jean Cocteau didn’t make very many films. After all, he had started out as a writer and only later went into film. That makes it all the more impressive, of course, that he had such amazing visual talent as a director (he made my initial Top 100 with only a handful of films). So, we have to treasure the few that we do have.

This film is a fascinating film that Cocteau adapted from his own play that, unfortunately, proves that directors who hire their lovers to act in their films aren’t always making the right decision. This is a very good film with a very good performance from Edwige Feuillere at the heart of it, but part of what keeps it from being a great film is Jean Marais in the other lead role. It is true that Marais had played the role on stage and that he had made a fascinating Beast in Cocteau’s masterpiece. But there, playing an assassin who stumbles into a strange role in life, he never quite seems to have a handle on things and when he’s on-screen the film doesn’t move quite as well. That’s a shame because it kind of wastes Cocteau’s elegant direction and Feuillere’s performance.

Feuillere is the Queen. Her husband is dead, but she can’t help thinking of him (aside from the portraits everywhere). One night, an assassination attempt occurs and through bizarre circumstances, the assassin ends up in the queen’s room. That would mean little if not for his amazing resemblance to her dead husband. She is taken, almost immediately, and she can’t help but wonder what life is throwing at her. What happens over the next few days encompasses them both in a strange web of desire and pain. It ends perhaps the only way that it can, with a double betrayal, and the pain of such emotions overcoming any possible pleasure.

It works, partially because of the scenario that Cocteau has constructed, but also because the performance of Feuillere. She is every minute believable, both as the woman who is so torn in her emotions, but also as the queen, who, in some ways, refuses to be ruled by anything, even her emotions.

The Eagle Has Two Heads by Jean Cocteau (1946)

Cocteau was a writer before he was ever a filmmaker. He has often been immersed in the past and in the world of myth (like his play Orphee, which he would also turn into a film). This play allowed him to kind of intermix the two in an interesting way. The play was inspired by two different historical events – the mysterious drowning of Ludwig II (which provides background for the play) and the bizarre, sudden assassination of Elisabeth of Austria.

In combining these two events – the background of a dead king / husband with the the political circumstances that would end in a royal assassination – Cocteau also manages to weave together ideas of love and loyalty, of heartbreak and betrayal. It is a small play, confined to the Queen’s bedroom and library and covers a few days in the lives of the queen and her would-be assassin.

The Adaptation:

Cocteau was apparently determined to rather stick to the three-act structure that he had used in the play, and that was mostly what he did. But that didn’t prevent him from opening things up a bit, especially at the beginning of the film. In a sense, it reminds me of von Stroheim’s famous quote about how Lubitsch shows the king on a throne and von Stroheim would show him in the bathroom first. With the opening up, we see the queen out in the wild, hunting, and it really opens things up.

The Credits:

Un film de Jean Cocteau. There are no writing credits but Cocteau adapted it from his own play.

State of the Union

This is a film that often gets overlooked in a couple of different ways. The first is that it’s a Capra film, but it’s not a major film – not one of his three winners for Best Director or his Jimmy Stewart classics. The second is that it’s a Hepburn / Tracy comedy, but it’s a different type of comedy that most of their pairings. It’s not a romantic comedy, but rather a political movie, and political comedies have always been a bit of a mixed bag. Yet, in a very weak year for comedies, it’s one of the best of the year and it’s a film that deserves to be more appreciated than it is.

This film, in some ways, is a bit daring. In some ways, it’s similar to The American President, a film about men running for president framed as a comedy. But this film is more daring in that it actually discusses the current political scene and the possibilities. It doesn’t just sweep things aside and pretend this is a made-up America. The players discuss the very real candidates of the day – President Truman himself, as well as the two major players in the Republican Party that the main character would have to go up against – Thomas Dewey (who had been the candidate in 1944 and would end up being the candidate in 1948, earning the nomination not that long after this film was released) and Robert Taft.

Spencer Tracy is the candidate himself, a self-made businessman who is willing to say what he believes. His mistress, played by Angela Lansbury, owns a powerful newspaper and is determined to arrange a deadlocked convention that will then have to turn to her lover and acknowledge his ability to rise above the factions of the party. This time Hepburn is the wife that Tracy has been neglecting and is pulled into the plan to make things seem like a united front (yes, there are definitely things in this film that still resonate for this year’s election). Tracy and Hepburn are both solid and Lansbury is quite good (all three win the Comedy awards at the Nighthawks in this weak year while Lansbury earns her third Nighthawk nomination in five years for Supporting Actress). The film veers away from the political scene when it tries to play more as a comedy (such as when Tracy, determined to win a bet, parachutes out of the plane he has been piloting, much to the worry of Van Johnson, an employee of Lansbury’s who has been pushed into the position of campaign manager). But when it sticks to the politics, it works at a level you wouldn’t expect of such a film.

Of course, they weren’t going to actually allow the man to be elected president. In true Capra style, he becomes determined to speak his mind, no matter what his handlers say, and that kind of plain, honest speaking marks the real end of his campaign (what a contrast to his year where the “honest” racist, horrific things that continue to spew forth from Trump’s mouth only make people love him). In the end, it uses a little too much Capracorn to really rise above a low-level ***.5. But it’s a more honest, more interesting political film than most that have come along, either before or since.

State of the Union by Russel Crouse and Howard Lindsey (1945)

This is actually a surprisingly long play, running 226 pages in the copy I am holding in my hand. It definitely overstays its welcome more than the film does, with scenes going on forever. It deals a bit more with the contemporary politics than the film does, with many of the more comedic scenes having been added for the film. This was even more daring than in the film, because the play came out in 1945, when Truman hadn’t been president for very long and there were far bigger questions about what standard-bearer would emerge for the Republicans. The play itself is generally viewed as a dig at Wendell Wilkie, the man who surprisingly ended up with the Republican nomination in 1940 in spite of a total lack of political experience. The play doesn’t have a big ending like the film does, and in fact kind of just continues to fade away during the final scene until you finally stumble towards the ending. It is definitely stronger in the first act when it focuses more on the political questions of the day. But it’s a solid enough play and could possibly find a revival today when you have inexperienced candidates determined to run for president without any business being in the race at all.

The Adaptation:

“Though the play was at most a mild satire of political opportunism, its political viewpoint was clear enough, portraying Grant Matthews as a moderate Republican whose liberal tendencies are challenged by his dealings with reactionaries and special-interest groups from the ‘lunatic fringe’ of American politics. He is allowed by his political bosses Kay Thorndyke and Jim Conover (Adolph Menjou) to criticize organized labor, but not to criticize big business, and he renounces his candidacy at the end so that he can speak out as he pleases. Capra made the theme of Grant struggling to keep his integrity under pressure darker and more pessimistic; while Grant in the play at least passively resists making deals with people he despises, keeping alive some measure of self-respect, Capra’s Grant Matthews makes deals and hates himself for it. The film not only added Grant’s description of himself as ‘dishonest’ and his apology to the American people but also amplified the impact of his self-abasement by having his remarks broadcast on national radio and television.” (Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success by Joseph McBride, p 539)

“Though Capra was rebuffed by the Writers Guild in repeated attempts to win a writing credit on State of the Union, Veiller and Connolly expressed willingness to share their credit with him, and Veiller told the guild Capra had been actively involved in the writing. One of the scenes Capra surely had a large hand in writing was Grant’s monologue to Mary as he lies on the floor of their bedroom on the first night they spend together in the campaign. It closely resembled the speech about being a ‘failure’ that Capra wrote and discarded for George Bailey in Wonderful Life, and its personal echoes for the Capra of 1947 are unmistakable: ‘The world thinks I’m a very successful man – rich, influential, and happy. You know better, don’t you, Mary? You know that I’m neither happy nor successful – not as a man, a husband, or a father.'” (McBride, p 540)

Those two quotes really say most of what I could say. The film focuses more on the comedy (notably the parachute scene) and opens things up considerably, getting away from the five locations that the play is stuck in. And in typical Capra fashion, the big finish, the apology, is a big speech made from the heart.

The Credits:

Produced and Directed by Frank Capra. Based on the play by Howard Lindsay and Russel Crouse, As produced on the stage by Leland Hayward. Screen Play by Anthony Veiller and Myles Connolly.

César

I have criticized the 1961 film Fanny for trying to cram an entire trilogy worth of films into the space of just two and a half hours. This is the film that is most clearly slighted by the compression. In the latter film, it seems that about a decade of time occurs. But in the trilogy we get a full 25 years and the child that was conceived in the first film and born in the second had now grown into a young man, and it is that growth that is so important for the resolution of the human emotions that run through this story. With his stepfather having died (without revealing to Césariot that he wasn’t his biological father), this young man is now faced with an identity quest – learning who he is and where he has come from. That leads to him seeking out his father, Marius, whose need to to go to sea in the first film was stronger than his love for Fanny and lead to the separation that ended with his son being raised by another man.

We need this conclusion to the story. We need this young man to find out who he is, to slowly learn more about his father without his father knowing who he is. We need their interactions so we can finally get a measure of closure for Fanny and her relationship with Marius. Some people never get to have a relationship with their first love. Fanny gets to have the son that she wanted and Marius fled for the love of the sea as he wanted. But both of them actually do love each other dearly, and they both love their son. And yet, the strongest love in the trilogy is from César himself, Marius’ father who has never stopped loving his son, his daughter-in-law or his grandson. They are the three people in the world he loves most dearly and he’s not certain which of them he loves the most.

This trilogy is a triumph of the talents of three people. The first, of course, is Marcel Pagnol, who wrote all three plays, adapted them all for films and directed this final film in the trilogy. The other two are the two leading actors in all three films: Orane Demazis, so stolid and dependable as Fanny and Raimu, one of France’s most famous actors, and who was already dead by the time these final two films finally played in the States. The writing and the performances from these two stars are the glue that holds this trilogy together and makes it, not three nice little films, but one moving story of a family over the course of two decades.

The Source:

characters created by Marcel Pagnol (1929)

Unlike the first two plays in this trilogy, the third one was not translated by Jay W. Lees as part of his thesis. As a result, if there is an English translation of this play, it is not currently in WorldCat and I suspect there might not be one.

I decided to leave that paragraph there even though there is a huge mis-conception in it. There was no third play, in spite of what Wikipedia says. Reading a book on Pagnol, it became obvious that he decided to write the third film straight as a screenplay, skipping the stage. So there is no play to compare it to, though, since the characters already existed, it does still count as an adapted screenplay.

The Adaptation:

Because there was no third play, there’s nothing to write about here. Certainly, as the author of the original two plays and their screenplays and as both the writer and director here, anything that Pagnol chooses to do with the characters clearly falls under the heading of “authorial intent”.

The Credits:

Marcel Pagnol présentent is the only credit for writing or direction in the opening credits (Pagnol did both).

The Snake Pit

I have reviewed this film once already. When I went back to it, after a long time had passed since the first time I had seen it, I was much more impressed with it than I had been on the first go around. It is a strong film, with an excellent performance at its heart from Olivia de Havilland. It is also a well-written film, one that really dives into the whole problem of mental health and how it is treated in this country, something which still resonates today.

The Snake Pit by Mary Jane Ward (1946)

I, quite frankly, expected a lot more from this book. It was a big success at the time, selling copies into the hundreds of thousands, being a Book-of-the-Month Club choice, and inspiring not only the film adaptation, but with the success of both the book and the film, inspiring actual changes at the level of treatment of mental health in this country. Given all of that, the book itself is quite a disappointment as a read.

Without getting into the autobiographical aspects of the book (I have always disliked biographical criticism), the book just doesn’t do enough for me to get into Virginia’s story. We start in first person, we end in first person, and there are occasional forays into it, but most of the book is told in third person and it makes it hard to focus on what is going on with her. She has clearly developed mental health issues and is in an asylum, but the narrative is so un-focused that it is hard to follow her journey. Now, you could make the argument that she is having mental health issues and her narrative should be un-focused, but I don’t think this is a narrative device here. I think it is just unfocused writing and it meanders all around. Eventually we can piece together some of the bits of her story and realize how she has ended up here in the “snake pit” (“Long ago they lowered insane persons into snake pits; they thought that an experience that might drive a sane person out of his wits might send an insane person back into sanity … They had thrown her into a snake pit and she had been shocked into knowing that she would get well.”). But I think the book would have been much more forceful if we had gotten it all in the first person point-of-view and really realized what had gone on to land Virginia where she is.

I know this book was written well before and I am loathe to hold up a book I don’t particularly like, but reading this, I can’t help thinking of The Bell Jar and how much a better job Plath did of helping us understand her character, what had happened to her and how she could have fallen off so far to end up institutionalized.

The Adaptation:

The first time I watched The Snake Pit, years and years ago, I had been impressed mostly with de Havilland’s performance. It was only going back to it for my Best Picture project that I realized how strong the film is as a whole and a lot of that comes from the writing. This is interesting because the screenplay does right what I think the book does wrong – provide us with a stronger narrative that makes it clear what has happened. What is more impressive is that the film does this without actually giving us a straight-forward narrative. We follow Virginia’s journey in its meanders, only slowly learning what has happened to her and it’s hard to trust her because she is an unreliable narrator. But, she is the narrator throughout the film and that gives the film a strong voice that the book lacked – we can actually follow her journey in her own words, rather than through a third-person narrative. Much of what is in the film does come from the book, chopped up into different parts, re-worked together in different orders (having recently seen Trumbo, it reminds me of him, chopping up his lines and taping them together).

In short, though the book was a big success, it really seems that the visual story, the clarity of how Virginia ended up where she is and the horrors she endures where she is, that really must have been the impetus for chance in the mental health system. In de Havilland’s performance, in the visuals, but most of all, in the writing, we can see the damage that such a system can actually do to a person and the sheer chance that someone like Virginia could ever actually come out of it with any sense of sanity intact.

One last note: “On THE SNAKE PIT, I rewrote the entire script – working closely with the director, Anatole Litvak, who was ‘too busy’ shooting to film to appear at the credit arbitration.” (Arthur Laurents, interviewed in The Hollywood Screenwriters, p 267). That’s one thing to bear in mind when it comes to the credits, not only on this film, but on lots of films.

The Credits:

Directed by Anatole Litvak. Screen Play by Frank Partos and Millen Brand. Based on the Novel by Mary Jane Ward. The IMDb does list Laurents as an uncredited “contributor to screenplay construction”.

Consensus Nominees That Don’t Make My Top 10:

I Remember Mama

This film isn’t quite sure what it is, which is perhaps reflected in its WGA nominations, nominated in both Drama and Comedy. Yes, there are a few comedic scenes, most notably those built around Oscar Homolka, the tyrannical Uncle Chris, the one holdover from the original 1944 stage production and the one who gives the best performance in the film.

Irene Dunne is the star of the film of course, as is always the case with a film (or play) that idolizes a parent and how they were at the center of the family. Her performance is quite solid but quite dour. It’s hard to look at that picture of her in my 1937 awards and then watch her in this film and see how such a seductive actress with impeccable comic timing is dragged into this tired role of the sainted parent, on her knees cleaning the floors when she can’t cope with not being able to see her child, the one that everyone turns to in times of need because she can hold things together.

We are also forced to endure a long and monotonous voice-over. These are memories of course, being brought to life by the young writer in the family and it really starts to drag after a while. This is the kind of film that today we would call Oscar bait and it did, of course, earn 5 Oscar nominations. It didn’t really deserve them (the only nomination it gets from me is for Supporting Actress and that’s more because of a lack of other worthwhile performances in the year – as I said, the best performance in the film is from Homolka) and eventually it wears you down.

I Remember Mama by John Van Druten (1944) which was adapted from Mama’s Bank Account by Kathryn Forbes (1943)

One nice thing about the published version of the play is a picture from the original Broadway production, and sitting there in the middle, playing the older son, is a young, already glowering Marlon Brando. Other than that, there’s not a lot of reason to go ahead and read this play. It makes it remarkably intact to the screen. Indeed, the film version of the play is a much closer adaptation than the play was the original novel.

The novel itself is really rather forgettable. It’s the same as so many other novels – a fictionalized version of the childhood written for rather young readers. It hardly functions properly as a novel – it’s more a collection of various little vignettes that follow no clear chronology. About half the vignettes make it into the play with varying degrees of fidelity. It was the play itself that really took the pieces and formed them into a coherent story, with a dramatic arc to them. The original book goes through a much longer period of time, all the way until the children have actually grown up and start having children of their own.

The novel itself is really rather forgettable. It’s the same as so many other novels – a fictionalized version of the childhood written for rather young readers. It hardly functions properly as a novel – it’s more a collection of various little vignettes that follow no clear chronology. About half the vignettes make it into the play with varying degrees of fidelity. It was the play itself that really took the pieces and formed them into a coherent story, with a dramatic arc to them. The original book goes through a much longer period of time, all the way until the children have actually grown up and start having children of their own.

I must not be the only person who has looked at the novel and wondered which parts of it went into writing the play. The copy I got from the University of New Hampshire has, on the chapter list page, little penciled in “NO” next to every chapter that was not included in the stage play (or the film, I suppose), which is Chapter 8, as well as Chapters 11 through 17.

The Adaptation:

This is a film that sticks close enough to the original play that you can go through long stretches reading along without a single change in a line. There are a few things that are changed a little to open things up, as things are always done with a play.

Perhaps the most notable change is one that was probably made to appease the Production Code. In the play, Jessie, the housekeeper for Uncle Chris, has been with him for 12 years but as companionship only, as “she has husband alive somewhere.” The Code wasn’t going to allow a relationship like that so, she couldn’t marry him at first, but then her husband died and they are married and she is introduced to the others after he dies as his wife.

The Credits:

Executive Producer and Director: George Stevens. Screen Play by DeWitt Bodeen. Based upon the play “I Remember Mama” adapted and directed by John Van Druten. From the Novel “Mama’s Bank Account” by Kathryn Forbes.

Sitting Pretty

I would say that Sitting Pretty is an astoundingly ridiculous film except for one thing: as part of the whole point of this project I read the original novel that it was based on. I will write more on that below but suffice it to say that as ridiculous as this film is (exceedingly) it is much less so than its source.

The problem is not that this film is so absurd – after all it’s a silly little comedy and isn’t really striving for anything more. It’s that it was apparently taken seriously by people who absolutely should have known better. I’m writing about it because the Writers Guild, a group of people who should be able to identify quality writing (notably absent here) nominated it as one of the best written American Comedies of 1948 and then even gave it their award. Even worse, for his performance as Lynn Belvedere, Clifton Webb was nominated for Best Actor at the Academy Awards. Is Webb somewhat charming as the mysterious man who loathes children but has nonetheless answered an advertisement to be a live-in nanny? Yes, he is, even if he seems to be a bit too trained for anything that might come along. But he was nominated over Humphrey Bogart, whose performance as Fred C. Dobbs in Treasure of the Sierra Madre is one of film’s greatest. How on earth did Webb end up on the list?

There are several things about this film which are ridiculous because of the book (see below), or in spite of the book (further below) but there’s one thing that is all the fault of this film. How to justify a marriage between the obviously middle-aged Robert Young and the young and very beautiful Maureen O’Hara? How is that possible? It made me pull away from the film from the opening moment.

This film is never able to rise enough about its source material to actually become a good film. Webb is too polished and refined to keep it from sinking any lower. Therefore it slides down into that lower echelon of *** films.

Belvedere by Gwen Davenport (1947)

My first experience with the character of Lynn Belvedere was in the television show (I originally wrote “short-lived television show” then looked it up and realized it ran for fucking years!). I had to be reminded by the Wikipedia page that Bob Uecker was in the show. All I actually remember about it was that there was a cute teenage daughter (that’s all I remember about a lot of shows – my brain tells me Tony Danza was on Who’s the Boss but all I can think of when the show is mentioned in Alyssa Milano). It seemed dumb and I didn’t watch it. It was very strange years later to learn that it had its roots in several films and even a book. I didn’t think they would be interesting. The film wasn’t that interesting. The book was worse. It’s about an uptight man who moves into a family’s house because they have advertised a room for rent for a writer that also involves some small nanny duties. He moves in, writes his book, becomes celebrated as a genius and then decides he will stay in the house to write the next two parts of his trilogy. All in all, just a silly little book that should have been quickly forgotten, yet it somehow spawned three films and eventually a television series. It boggles the mind.

The Adaptation:

In Belvedere, Lynn Belvedere ends up tending to three children because he wants a quiet place to write the brilliant novel that he has already completed in his head. Therefore, we know precisely, from his arrival, why he would take the job. That gives the novel one leg up on the film, as we spend of the film wondering, like the parents, why this man would ever want to take this position, let alone fight so hard to keep it. But by changing the wording of the advertisement, the filmmakers also add a bit of mystery to what is otherwise an extremely flat story.

The Kings have advertised for a live-in nanny and this is what they got. They (and us, the audience) wonder what he could possibly be doing up in that room. In the book, he is writing David Copperhead, which is immediately hailed as a work of genius and then he decides to stay where he is to complete his trilogy. He’s been telling people that what the book is and so it’s no surprise when that’s what he publishes. The film decides to do something more – Belvedere’s book is a tell-all about everyone in the Kings’ neighborhood. That brings him fame, but also scandal, and Mr. King is fired from his job and his former boss threatens to sue Belvedere. None of that is present in the book and it’s all kind of silly on film, but it at least provides a bit more of a story. As silly as it is, it doesn’t just fall flat like the last half of the book does.

The Credits:

Directed by Walter Lang. Screen Play by F. Hugh Herbert. Based on a Novel by Gwen Davenport.

Johnny Belinda

I have reviewed this film once already. Watching it again, it didn’t sit any better with me – Wyman’s performance is just not enough to overcome the massive hits of melodrama beating you over the head while you’re trying to watch it.

The Source:

Johnny Belinda by Elmer Blaney Harris (1940)

If you think the movie is problematic, hitting you over the head again and again, it’s actually got nothing on the play. There is only one thing that the play does better than the film and I’ll mention that below. But, in the play, she’s not really Belinda. She’s the dummy, so called by everyone in the play before the doctor finally starts setting people straight and making people realize that she’s a real woman, intelligent and worthwhile, outside of her inability to speak or hear. There is not subtlety at all in the play and I’m rather surprised that it managed to be a success at all, yet, it must have been at least somewhat of one, not because it was made into a film (lots of plays that don’t even get produced end up being made into films), but because it is actually still in print.

The Adaptation:

As with most plays that are adapted to screen, a number of scenes are opened up, some scenes are compressed and some scenes are decompressed. Most of the dialogue in the film comes from the play as well as the storyline. But there are a couple of changes, one for the worse, and one for the better. The one for the worse is that the trial scene in the play is very short, a little coda at the end of the play, and in which Belinda has already been cleared of all the charges – it’s in there just to make the ending of the play clear, while in the film, it’s a bunch of melodrama tacked onto the end in case we haven’t been bludgeoned enough by it already.

But there is a much bigger change which makes the film better than the play. In the play, the father goes offstage and then we are suddenly told that he has been hit by lightning and killed. People who have already seen the film might suspect that the father has been killed by Locky, the brute who raped and impregnated Belinda, but no, there are actually several witnesses – the father is, in fact, killed in a freak accident. The film takes away that strange event and actually has the father realize the truth about what has happened and when he goes to confront Locky, he is killed in the struggle that ensues. That makes the father a stronger character (helped by the performance by Charles Bickford) and while it adds even more evil to Locky, it is not out of character for him and it gives some more weight to the melodrama that follows.

The Credits:

Directed by Jean Negulesco. Screen Play by Irmgard Von Cube and Allen Vincent. From the Stage Play by Elmer Harris, Produced by Harry Wagstaff Gribble.

Oscar Nominees That Don’t Make My Top 10:

The Red Shoes

I have reviewed this film once already. As I mention in that review, I think much more highly of this film than I did the first time I saw it. It is beautiful and vibrantly alive. It will never be a great film to me, not because I don’t like ballet (which I don’t), but because the story and the acting never rise above okay. In fact, a number of Michael Powell films might have been better if he had been blessed with the kind of acting regulars that Bergman or Kurosawa had.

“The Red Shoes” by Hans Christian Andersen (“De røde Skoe”) (1845)

In the Norton Annotated Hans Christian Andersen, this is the first story in the second section, the Tales for Adults section. I will quote from the introduction to that tale by the fairy tale expert, Maria Tatar: ” ‘The Red Shoes’ is one of the most disturbing tales in the literary canon of childhood, and it has been read in multiple ways, but always with attention to the horrors of the chopped-off feet that dance on their own. Today, Karen’s dance in Andersen’s tale is read less as an act of insolent arrogance than as an expression of creativity.”

It is certainly one of Andersen’s more brutal tales, almost more akin to what you would find in Grimm than in Andersen. It is the tragic tale of the little girl who at first had no shoes, than has a pair of red shoes given to her and destroyed, before she gets the shoes of the title, the ones that will break her. They begin to dance and there is nothing she can do but endure what she can, dancing towards the dead, dancing against god, and then, with the lurid image it creates, we get this: “Karen confessed her sins, and the executioner chopped off the feet in those red shoes. And the shoes danced across the fields and into the deep forest, with the feet still in them.” Then we come to that final image which does seem to fit more with Andersen than with Grimm, of peace in the everlasting: “Her heart was so filled with sunshine, and with peace and joy, that it burst. Her soul flew on the rays of the sun up to God, and no one there asked her about the red shoes.”

quotes from the Annotated Hans Christian Andersen, translated by Maria Tatar and Julie K. Allen

The Adaptation:

Is this really an adaptation? It does not actually mention the Anderson story in the credits and it was nominated at the Oscars for Best Original Story. To be fair, the story, as used in the film, is original, but today the Academy would almost certainly qualify this as adapted, so here it is.

The film uses the original fairy tale as a jumping-off point. It incorporates the tale into the ballet that is at the center of the film and then carries it further with the horrible fate that awaits the dancer who can not seem to stop dancing. There have been any number of films adapted from fairy tales but few use them as originally as this one does.

The Credits:

The Entire Production Written, Produced and Directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger. From an Original Screenplay by Emeric Pressburger with additional dialogue by Keith Winter. The only mention of the source material is during the title shot, with the candle sitting on a book labelled “Hans Christian Anderson”.

WGA Nominees That Don’t Make My Top 10:

All My Sons

They really want you to know that this is an “important” picture. Look at the poster right there, and see the “New York Critics’ Award Play” right at the top. This is serious art, after all. Yet, it never really found traction – it only earned a single WGA nomination from awards groups and for a long time was unavailable on DVD (from the cheapness of the DVD I watched, I suspect it’s actually out of copyright). Yet, this is an overlooked film, a very good little film with one of the last really strong Edward G. Robinson performances. It’s a reminder that he didn’t need to go back to a gangster role for Key Largo when he could still give a strong performance like this one in a more serious film.

Robinson plays a man with two sons. One of them died during the war, but with no body ever found, his wife continues to believe that he may come back to them any day now. His other son idolizes his father, who worked in production during the war, providing machinery to the military. Now his son wants to marry the woman who used to be his brother’s girl. It’s complicated by the fact that her father went to prison for shoddy production from the company co-owned by him and Robinson and there’s the question over whether or not Robinson was in fact responsible (he had a trial and was found innocent).

Robinson plays a man who has deluded himself into believing that he has done what he needs to do to provide for his family. Yes, he knew about the problem, but to fix it would have probably cost him the factory and cost his family their welfare. So he did what he convinces himself what was right. That soldiers died, that his partner went to prison, that lives were lost and shattered, are something he has learned to live with. But his son doesn’t know all this, and it is the story of how his living son finds out the truth and confronts it is the real drama in the play, the kind of drama that Henrik Ibsen was so good at and Arthur Miller would prove to be a master of.

Unlike Tennessee Williams, Miller plays weren’t constantly made into plays (there are also fewer Miller plays). We should therefore treasure the ones we have, especially when they have as compelling a performance as the one from Robinson here, the kind of performance he seemed to have lost in his later career (at least when not working with Fritz Lang). So, if you get a chance this is one the WGA got right – this film really does ably deal with the problems of the American scene and it should be seen. Go find it.

All My Sons by Arthur Miller

This is not yet the Arthur Miller as we have come to know him. This was his first success, his final try at writing a commercially successful play or he was going to give it up. Thankfully, it was a success and what followed was the third part of the great American triumvirate of playwrights.

The influence of Henrik Ibsen is apparent throughout the play. It is a very heavy play, dealing with the problems of a family as wells as the problems of giving a part of yourself up in order to achieve the American Dream. This, perhaps more than any other Miller play, feels like what Ibsen would have written had he lived in America in the 20th Century. There’s nothing wrong with that of course – Ibsen is one of the greatest playwrights in history. But Miller hadn’t quite found his own footing yet, in spite of how good this play is (very good). That would come in his next play, in which the themes begun in this play come to full fruition: Death of a Salesman. Indeed, the confrontation scene in this play between father and son would set the stage for the much more brutal one that would follow in the later play.

This is a play that is still performed, and with good reason. It’s the story of a man who let the government put shoddy materials in the war and lead to the death of American soldiers. He did it to save his business and his family. To keep it quiet, he sacrifices his partner. The events of this play are when the truth of this come out, affecting the son who survived the war and, we discover, having affected the son who didn’t survive.

Most of my Drama collection I got rid of in the last few years in the realization that I don’t need to save all these books when I’ll never have a university office to store them in, to bring out for classes. But I have kept all the Miller plays (in spite of having many of them in the Portable Arthur Miller) because they are so good, they are worth reading, and hell, in their matching Penguin bindings, they look cool on the shelf.

The Adaptation:

As the first film adapted from a Miller play, director and writer Chester Erskine wouldn’t feel the need to stick as closely to the original play as later writers would do. They stuck very close to the plot. They even kept the very bleak ending that perhaps kept the film from being a bigger hit. But a lot of the scenes are altered, especially the long opening scene of the play which is mostly dropped in order to drop us straight into the action of whether or not the son will marry his dead brother’s girl.

The Credits:

Directed by Irving Reis. Based on the play by Arthur Miller, as Produced on the stage by Harold Clurman, Elia Kazan, Walter Fried, Herbert H. Harris, Critic’s Prize Award for 1947. Written and Produced for the Screen by Chester Erskine.

Call Northside 777

This is a film that reflects its times, a type of film that doesn’t really get made anymore, and really wasn’t made for very long. It’s a film that seems like it comes from one of those old March of Time films, a film that tells a “true” story (events have been somewhat fictionalized) of a true crime and the efforts from one reporter, first, to find out the truth, and then, to see justice done.

It was directed by Henry Hathaway, and that might say it all. Hathaway was never a great director, but he was an extremely efficient director who made technically sound films and they were usually worth watching, even if there was no snap to them. That makes him the perfect director for a film like this. And it starts Jimmy Stewart, who is probably the perfect star for a film like this. He gets introduced to the story in a roundabout way and then decides that it’s important to know what really happened (he is a reporter, after all), and then, he continues to fight for the truth to come out. It’s competently acted all around, solidly made, solidly written.

As I said, they didn’t really make these kind of films for very long, namely because the whole style, with a voiceover narrator explaining every step of the process, would soon become ripe for parody. But, for a short time, in the late 40’s and early 50’s, there were a number of them, most of them solidly made, and this might very well be the best of them.

The Source:

Chicago Daily Times articles by James P. McGuire and Jack McPhaul (1944)

Ah, here is where we reach the limits of what I am willing to do for this project. This film is based on newspaper articles that detailed the actual events that are somewhat fictionalized in the film. I am not willing to go and track down the original articles, mostly due to time constraints.

The Adaptation:

Without the original articles, of course, I can’t be certain of how well they were translated to film. But, at the very least, some of the events were fictionalized, with some time compression and some events altered.

The Credits:

Directed by Henry Hathaway. Screen Play by Jerome Cady and Jay Dratler. Adaptation by Leonard Hoffman and Quentin Reynolds. Based on Articles by James P. McGuire. The IMDb lists uncredited writing from Jack McPhaul.

Command Decision

In the 1930’s, Clark Gable was one of the biggest stars in Hollywood, and in films like It Happened One Night, Mutiny on the Bounty and Gone with the Wind he combined star power with great performances. In the early 1940’s, Sam Wood was one of the biggest directors in Hollywood. In the space of five years, 1939-1945, he directed six films that were nominated for Best Picture, a mind-boggling level of success. But by 1948, neither was doing all that well. Gable’s acting skills had decayed into pure bluster. Wood had never actually been that great a director and after 1946 his films would earn no more Oscar nominations. This film combines them and it’s not that impressive (it’s my #72 of the year, a low-level ***).

That poster on the right might say quite a bit about this film. This is supposed to be a serious film about a general who is pushing his flyers too hard late in World War II. He’s trying to knock out Germany’s ability to produce a new plane that is much faster and can go much farther than anything the Allies have. But his men have a breaking point and there is a balance to be found in how hard you can push your pilots before they break and you lose the ability to get the performance out of them that you need. But those faces are smiling as if this were a carefree film. It deals with decisions by commanders that mean lives, it deals with the stress placed upon men in combat and it deals with the ability for this news to be properly reported. That last is important because Charles Bickford, who plays a key role but is not actually one of those pictures, plays a reporter who has to find a balance between what people need to know and when that information could impede the war effort.

But all of this is handled so indelicately. Gable isn’t the only one going through the film on pure bluster. He’s squaring off against two other commanders, played with almost equal bluster by Walter Pidgeon and Walter Donlevy. Supporting them is Van Johnson, who was never a great acting talent, as the desk sergeant who is Gable’s aide. It’s hard to get too involved in the story when it keeps trying to hit you over the head. It’s also easy to see, from the way it is set-up, that this was originally a stage play. It just feels so confined and it never breathes.

Command Decision by William Wister Haines (1947)

This is a novel, but it comes out of a play and would go back into being a play before being turned into a film. So, what it really has is a whole lot of dialogue and a lot of dialogue that wants to be more dramatic than it is. It really is a novel about two generals yelling at each other for long stretches of time with a few chapters thrown in during which the generals yell at other people. It lacks the kind of drama that it might have had on stage and didn’t on film because of the lackluster direction and the overly bombastic performances.

Yet, it must have been quite popular at least at first, if the copy I am using is any example. The book was published in 1947 and pencilled in the card slip of the Amherst College copy is 2/24/47. The book was then checked out seven times before July. And, because it is a really old-fashioned card slip it has two cards – one for the library and one for the borrower, with the signature on both, and those are seven different people checking it out. After that, it seemed to have gone dry, with it being checked out in 1949, 1951 and 1964, and though it’s possible someone got to it since they went to electronic records, it might very well have been over 50 years since this particular copy of the book was last read.

The Adaptation:

Most of the film does come straight from the book. There is one very important scene that is changed though. When Gable’s character discusses one of his men being in trouble and his staff sergeant asks for permission to use some ice cream and deal with the issue, in the book this is in reference to a rape. This is not reading into the situation, this is literal: “A navigator raped somebody between yesterday’s mission and today’s? Who’s complaining, the girl or her mother?” Naturally the word rape is completely dropped and the situation is made much lighter. It was a shock to even see it in the book at this time period. It did make it into the play, though.

The Credits:

Directed by Sam Wood. Screen Play by William R. Laidlaw and George Froeschel. Based on the Play by William Wister Haines. As Produced on the Stage by Kermit Bloomgarden.

Sorry Wrong Number

Sorry, Wrong Number is a solid thriller (my #43 of the year) with a good performance from Barbara Stanwyck. It’s a reminder that Stanwyck was a rare actress, the kind of person who can be strong even when she’s weak and is not to be underestimated. In the end, it’s not enough to save her from the circumstances, but it does make for a much more interesting film than it might have with a different actress in the lead role.

Stanwyck plays Leona Stevenson, the kind of woman who lies in bed and gets other people to do things for her (she physically is restricted to bed, so that’s not necessarily laziness on her part). She is the kind of woman who will marry a man to steal him from another woman, who will marry a man in spite of the objections of her father, and yet, will have a framed picture of her father as the most prominent thing in her bedroom rather than one of her husband. She’s strong and resourceful, even if she’s physically weak. Unfortunately, she’s also in danger. Her husband, one of the weakest men ever played by Burt Lancaster (it’s understandable this early in his career – I don’t think he would have worked in this role later) is in a lot of trouble and that’s going to put her in that danger.

All of this works to make for a successful thriller, especially as things countdown to the final moments, where we know what is going to happen, where the characters slowly start to realize the danger they are in, and things come to a head. It’s not a great film, far from it, and I’ll discuss why in the adaptation section below. But it is a good film, a very watchable film and Stanwyck delivers a solid performance. It might not have been worthy of its Best Actress nomination (she comes in 7th on my list) but it was close.

The Source: