My Top 7:

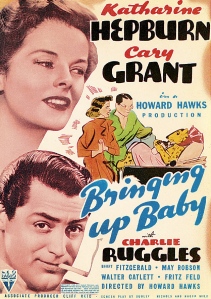

- Bringing Up Baby

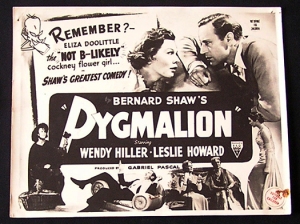

- Pygmalion

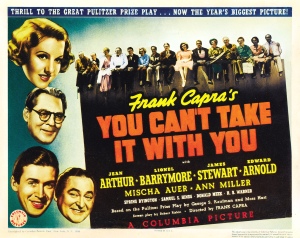

- You Can’t Take It With You

- Merrily We Live

- The Adventures of Robin Hood

- Bluebeard’s Eighth Wife

- The Citadel

Note: Remember that this list is in order of my rank for the Screenplay, not for the film itself. Otherwise, Robin Hood would be first. But the wit and humor of the other scripts manage to overcome the script for Robin Hood, a film that is lifted in its overall quality by its direction and technical marvels. Also, remember that while four of these films were nominated for Best Picture (You Can’t Take It With You, which won, Pygmalion, Robin Hood, Citadel), Merrily We Live was not, and yet received more nominations than three of the four Picture nominees listed and the other two films (Bringing Up Baby, Bluebeard’s Eighth Wife) weren’t nominated for any Oscars at all.

Oscar Nominees (Best Screenplay):

- Pygmalion

- The Citadel

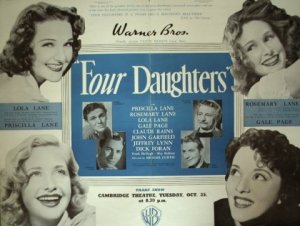

- Four Daughters

- You Can’t Take It With You

Analysis: George Bernard Shaw sets a new mark for a major author known outside the film industry by winning the Oscar, something that John Irving would also do, but as the previous post demonstrated, usually ends in failure (Shaw is the only Nobel winner to win an Oscar, unlike Faulkner, who was never nominated or Steinbeck, who was but didn’t win). We still have some category confusion – Boys Town wins Best Original Story and is nominated for Best Screenplay, but clearly isn’t adapted. Pygmalion, the winner, was the only one of the nominees not nominated for Best Director.

The Film:

This is one of the few films on this list that I haven’t reviewed before. So why is that, when it’s got the best script (I was going to say is the best of the lot, but I still have it ranked slightly below Robin Hood overall)? Because, unlike a lot of these films, it wasn’t nominated for Best Picture. In fact, it wasn’t nominated for anything at the Oscars that year. Which, I guess, goes to show how much the Academy knows.

There are a lot of genres (I go with 14, not including Foreign). Within those genres, there are a lot of sub-genres. And surely one of the most enjoyable is the Screwball Comedy, the “must-try-to-stop-laughing-before-I-pee-myself” version of the Romantic Comedy. The main characters are usually just that – a couple of characters, and romantically involved to boot, whether they are romantically inclined or not. And then things tend to get screwy. The actual phrase seems to date (according to the OED) from 1938, the same year that Bringing Up Baby would be released and would promptly lose money (and pretty much drive Hepburn off the screen for two years). Which, I guess, goes to show how much audiences know.

It’s one of the best of the Screwball Comedies, a complete nut-house from start to finish. It’s the story of a beleaguered professor just trying to get his final bone for his Brontosaurus and maybe a million dollars for his museum. But he has the bad luck to run into Susan Vance, a complete and utter screwball; she’s the kind of woman who drives off with the wrong car or doesn’t realize that the back half of her dress is suddenly missing. It was good enough to get Cary Grant as poor David Huxley, just trying to get his bone. But to also cast Katharine Hepburn and allow her, after years of dramatic roles, to find the absolute perfect comic timing as the airy rich girl who suddenly wants something only to have that something(one) keep running away from her as fast as he can was pure cinematic brilliance.

Then there are the other aspects. There is the rest of the story – how David and Susan must deal with a leopard named Baby (and later, another, much more violent leopard) while trying to get David’s bone and dealing with all manner of other nuts, whether it be Susan’s rich aunt or the complete bumbling idiot of a constable – and all of it just keeps you laughing through every minute. There is the directing from Howard Hawks, who had already proven himself as a first-rate gangster director (Scarface) and would later make classic comedy (His Girl Friday), drama (To Have and Have Not) and mystery (The Big Sleep) films as well. It’s got brilliant editing that knows exactly what to show. When there is a crash of a truck carrying chickens, we see David and Susan trying to hold back Baby. Then we see her escape. The next shot is David, covered in chicken feathers. We don’t need to see the slaughter. The cut is perfect exactly how it is (or later, when we don’t see Susan wrangle the nasty leopard – we only see her dragging into the police station).

In hindsight, we can see what the Academy and audiences could not see in 1938. That Bringing Up Baby is the best-written adapted screenplay of the year, that Hepburn and Grant easily deserved Oscar nominations for their brilliant comedic portrayals and that the film is easily one of the best of the year, better than the Best Picture winner (You Can’t Take It With You), much much better than several of the nominees and only surpassed by 2 of the 10 actual Oscar nominees (Grand Illusion and Adventures of Robin Hood). From start, all the way through to its brilliant finish, it is one of the most enjoyable comedies ever made.

The Source:

“Bringing Up Baby” by Hagar Wilde (1937)

“Bringing Up Baby” was a short little four page story that ran in Collier’s on April 10, 1937. It was about a young woman whose brother sends her a panther, intended for their aunt. The woman brings in her fiancee, they manage to lose the panther in Connecticut and then when they find it and give it to her aunt she thinks they’ve simply managed to find one for her. The couple live happily ever after and the aunt decides to leave all her money to her niece instead of her nephew.

The Adaptation:

As I said, it’s a short cute little story. But somehow Hagar Wilde (the original author of the story) managed to team up with Dudley Nichols (Oscar winner for The Informer, a far different kind of film) and make an absolute screwball classic from it. There are a few things that do come straight from the story (including how when Susan is told she must leave the apartment, she replies “But I have a lease.”). But the big difference is that in the story, David is Susan’s fiancee – there is no other woman, no one that Susan has to steal him away from. And he’s not clumsy or shy – he’s just her fiancee who is there to try and help. There is an essential framework there in the story, but nothing to show what kind of classic it would be on film.

The Credits:

Directed by Howard Hawks. Screen Play by Dudley Nichols & Hagar Wilde. From the Story by Hagar Wilde.

The Film:

I have already reviewed this film once. I pointed out that I really enjoy the film, especially enjoying the two lead performances, but I find myself missing the songs. When Higgins complains about the English not knowing how to speak, I expect the song. When “the rain in Spain falls mainly on the plain” I expect it to do so to music. It’s a great film, with a great script, and if the absence of the songs is something that affects it, it doesn’t detract from the great wittiness of Shaw’s lines and the way they are said by Howard and Hiller.

Pygmalion by George Bernard Shaw (1912)

Oh what a wonderful play. Everything you know in My Fair Lady comes from this play, except the songs. But how rare is it to have a play transformed into a musical and have so much of the original dialogue still be there? Pygmalion is brilliant not for the story (which is centuries old), but for the Shavian wit, for the clash between Henry Higgins and the creature he creates, the creature he falls in love with, the creature who manages to become his equal, bantering with him back and forth at the end like he probably always hoped that she would. Although, there is one advantage of not having the songs in the original play – no “Get Me to the Church on Time”.

The Adaptation:

It’s so interesting because of those credits. Shaw wrote the original play of course and he is credited with the adaptation and dialogue, for which he won the Oscar. So what exactly is the scenario that supposedly the other writers wrote? Indeed, much of the screenplay came straight from the play, exactly as Shaw had written it, with some lines moved around slightly. And when Shaw did change things, he decided that he liked them, because he would re-issue the play with his script changes intact in the play.

But the big change comes at the ending of course. In the play, Eliza didn’t stay with Higgins – she went off to marry Freddy, with Higgins roaring with laughter at the thought of it concluding the play (when I needed an off-stage character for a love interest to marry in a story of mine I chose the name Freddy for this very reason). But the film is where we find the ending that I think most people really wanted. And yet, we still have to keep to the characters, have Higgins turning away from her, even with her love offered to him and him accepting it, and have him utter that memorable line “Where the devil are my slippers?”

The Credits:

Directed by Anthony Asquith and Leslie Howard. Screen Play and Dialogue: George Bernard Shaw. Scenario: W.P. Lipscomb and Cecil Lewis.

The Film:

I have already reviewed this film once. It didn’t hold up as well on a second viewing, wasn’t as good as the best work of Capra and has more of the “corn” of Capracorn than the other films. But it was interesting to go back this time and see the ways in which it became more Capra in the film than it really was Kaufman and in this third viewing, it perhaps went back up a little. This is one of those films where Capra’s name was indeed above the title, and I think, watching the film and reading the play, it really does belong there.

The Source:

You Can’t Take It With You by George Kaufman and Moss Hart (1936)

You Can’t Take It With You won the Pulitzer Prize in 1937 and then would go on to win Best Picture when it was adapted into a film – the first time this would happen. It’s a fun play about a free-living family, several generations of which are all gathered together under one remarkable roof. The family is suddenly forced to interact with a prominent rich financial family when the older granddaughter becomes engaged to the son of the family. The granddaughter, Alice, has really been the only link to the “real world” outside the door of the house and everything we would imagine when two such different families come up against each other pretty much does happen. It won the Pulitzer not because it has much of anything profound to say (although perhaps saying we don’t need to care about money to find happiness in the middle of the Depression was considered profound) or even how it says it, but because it gives it us memorable characters and finds ways to make them unhappy and then happy again before giving us a nice ending that ties everything up together.

The Adaptation:

Like with many of Kaufman’s plays, there are actually significant differences between the play and the film version. The first is in the setting. Like with Stage Door, Take is actually a play that only has one setting – this one being the house. But, like with the film version of Stage Door, there is a lot of action that takes place outside the play’s setting. Indeed, the entire first part of the film takes place at Kirby’s office where we slowly get to learn about Kirby, then his son, and only then do we see the son interacting with his secretary and we realize how much in love they are. And that gets to the next part – in the play we begin with the Vanderhoff house and the family. We only learn about the Kirbys second-hand at first and then later, after they show up, do we get to know them a bit. But here, Capra and Riskin (his regular screenwriter up this time) establish the Kirbys first, for all their strengths and flaws.

That also brings us to the second major difference between the play and the film. In the film there is an entirely added subplot about Mr. Kirby wanting to buy up a bunch of land and this house being in the middle of it all. So, instead of just dealing with a romance between two people from very different backgrounds, we also have a great deal of tension at the center of the play, and not just tensions caused by different philosophies. So, it is to Riskin and Capra’s credit that we manage to somehow bring ourselves back to that happy ending that we saw in the original play. In fact, given the much higher level of tension added in the film, Riskin and Capra do an even better job of supplying us with the happy ending that we are going to want from this kind of film.

The Credits:

Directed by Frank Capra. Screen Play: Robert Riskin. Based Upon the Play by George S. Kaufman and Moss Hart.

The Film:

I have already reviewed this film once. I talked about the quality of the film and about what made it such a good screwball comedy. But I didn’t mention the plot much – which is about an eccentric rich woman who takes in hobos to work in the house in order to help them out. This time she finds one by accident (his car has died, literally, and he has knocked at the house to use the phone) who also happens to be articulate and handsome (he’s a writer), who of course falls in love with the elder daughter and who falls in love with him. Sound somewhat similar to My Man Godfrey? Well, it is, though the source actually pre-dates it.

The Dark Chapter: A Comedy of Class Distinctions by E. J. Rath (1924)

As I said, The Dark Chapter, the source novel, actually pre-dates the novel My Man Godfrey by a decade. And so, you could say that Godfrey stole some of its ideas from this novel (which would also become a play and two different 1930 films). But it has another similarity with Godfrey – it is not particularly memorable as a piece of fiction, isn’t that well-written and would probably be forgotten today (not that it’s much remembered) if not for the film version. It’s exactly what the film would become – a story of a tramp who comes to live in a rich family’s house and who would end up falling in love with the daughter (who would also, of course, fall in love with him). Although, unlike the film versions and Godfrey, it was written in the 20’s and so didn’t have any of the Depression in the background making the whole thing seem slightly inappropriate.

The Adaptation:

There isn’t a whole lot of difference between the novel and the film. The key difference is the presence of the wise-cracking younger sister – that’s purely an invention of the filmmakers, and as played by Bonita Granville, of course, is a fantastic invention (perhaps they were inspired by her similar role in It’s Love I’m After). The other big difference is the ending – the end of the book entirely hinges around the actual proposal between Rawlins and Jerry (Hilda in the book) while in the film, we end with a much funnier note dealing with Grosvener, the poor embattled butler.

There is a second source as well – the play They All Want Something: A Comedy in a Prologue and Three Acts. It was written by Courtenay Savage in 1924 and is adapted from The Dark Chapter. And yet, the play is far more similar to the original novel than it is to the film. All of those things mentioned above are missing from the play as well.

The Credits:

Directed by Norman Z. McLeod. Screen Play by Edie Moran and Jack Jevine. no source credits.

The Film:

I have already reviewed this film once. This is what I wrote about it, in summation: “What do you want from a movie? There are times when I just want to enjoy myself. And few films fit that description better than The Adventures of Robin Hood. It is the best of all the Errol Flynn films, made with masterful direction from Michael Curtiz and exquisite technical mastery. It is a great film through and through.” That pretty much sums it up – a film that I have loved from the first time I saw it and a film I continue to love every time I see it.

various Robin Hood stories and legends

If the Academy considered O Brother Where Art Thou as adapted then it’s gonna consider every Robin Hood film as adapted in my mind, and so that’s what I’ll do. But adapted from what, precisely? Unlike the Arthur legends, which similarly tell British history and have changed over time, there is no definitive point, no Mallory to point to. The origins of Robin Hood are shrouded in mystery but appear to be at least 900 years old. But various elements derive from different points in time. The idea of Robin Hood fighting during the time of Richard’s absence and the presence of Maid Marion date to the 16th Century. The concept of Robin fighting for the Saxons and being “Robin of Locksley” seem to date to Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe, which was published in 1819. Howard Pyle’s 1883 novel The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood (the Illustrated Junior Library edition, pictured to the left, is the one I grew up with) is probably the defining modern text and many of the story elements in this film come from that book, though Pyle didn’t much deal with the Crusade idea.

The Adaptation:

Several of the story elements in the film come straight from Pyle’s book, even though they are also in other sources. The fight against Little John, the bonding together of the Merry Men, the first meeting with Friar Tuck, the wooing of Maid Marian, with the eventual blessing from King Richard, and the battles against the Sheriff all hail straight from Pyle and are fairly close to his versions. But other parts of the film aren’t in Pyle at all and are an amalgamation from other sources. In the film, Robin is trying to maintain the land for Richard, the “true king” and he deals with Prince John. But Pyle’s book begins “when good King Henry the Second ruled the land”. Henry II dies on page 262 and Richard becomes King but “though great changes came, they did not reach to Sherwood’s shades, for there Robin Hood and his men dwelled as merrily as they had ever done” and when Richard comes to Sherwood at the end, he has not yet gone to the Crusades. The script is a good combination of the Pyle novel and those aspects of Robin Hood that been established by Ivanhoe.

The Credits:

Directed by Michael Curtiz and William Keighley. Original Screen Play by Norman Reilly Raine and Seton I. Miller. Based Upon Ancient Robin Hood Legends.

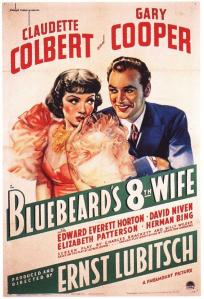

The Film:

There is a lack of critical consensus on this film. When I listed it at #8 on the year in my Year in Film post, I was thanked for recommending it by one reader, who commented that he couldn’t understand the two star reviews from Allmovie and Leonard Maltin. And just look at what Pauline Kael had to say about it in 5001 Nights at the Movies: “A miscast Gary Cooper in a flat comedy.” But Billy Wilder described it as “very very funny” and a weaker Lubitsch picture but one of his better ones (which I don’t agree with on either front). So, who to believe? Well see it for yourself and decide. But here’s what you’re getting into.

Gary Cooper isn’t miscast – he’s perfectly cast as an American who really doesn’t belong in France, who really doesn’t understand how to interact with other humans very well but finds himself falling in love all the time. He falls instantly in love with Claudette Colbert and because of that ends up intertwined a bit with her father (played well by Edward Everett Horton who has a great bit at the end of the film where he constantly enters a room, mutters the same thing and leaves). Colbert is all set to marry Cooper when she finds out about his past and she doesn’t know what the hell to do. So the rest of the film is that brilliant mixture of two people who really want to be together and really should be together finding different ways to keep themselves from being together while simultaneously finding ways to be together.

This is a mix of what would later be a Wilder film with what makes a Lubitsch film. It has some of the hilarious gags we think of with Wilder but it has more of a Lubitsch sensibility about it – it doesn’t have that dark streak of cynicism that would became the trademark of Wilder’s films. As a screwball comedy it’s not a complete classic – certainly nothing on the level of Bringing Up Baby. But it’s a high-level ***.5 film, a very good comedy and it’s good fun.

The Source:

La huitième femme de Barbe-Bleue by Alfred Savoir, tr. Charlton Andrews (1921)

The original source play for this film, while translated into English, doesn’t appear to have been published in English. If so, it certainly isn’t available.

The Adaptation:

Of course, it is difficult to say what might have changed in the course of translating the play into the film. How much can we assume came from the original play and how much from Billy Wilder and Charles Brackett, a writing combination who would go on to win two Oscars writing together (The Lost Weekend and Sunset Blvd.). Was the quick turn, where Gary Cooper looks at Edward Everett Horton’s pants, is apprised of the situation, and then tells him “I’ll buy the bathtub,” something from the original play? Could the original writer, be it Savoir or Andrews in his translation, have come up with the perfect idea of Horton constantly entering and re-entering the room at the end of the film or does that come from the genius of Wilder and Brackett? We know the beginning of the film did come straight from Wilder because he told us so in Conversations with Wilder (a book every film lover should own).

The Credits:

Produced and Directed by Ernst Lubitsch. Screen Play by Charles Brackett and Billy Wilder. Based on the Play by Alfred Savoir and the English Adaptation by Charlton Andrews.

The Film:

I have already reviewed this film once. I pointed out that it was the kind of role that Robert Donat was so perfectly suited for and it was a film with good writing and solid acting but didn’t quite make it into the ***.5 range (and thus qualify for Best Picture at the Nighthawks) because of weakness in the direction – it is directed by the over-rated King Vidor, after all.

The Citadel by A.J. Cronin (1937)

In some ways, The Citadel is like a weaker younger brother to Arrowsmith, the Sinclair Lewis novel that won the Pulitzer Prize and was made into a Best Picture nominee in 1931. It is the story of a doctor who at first helps the poor in a small mining town and then eventually, after he marries, decides to do easy work for the rich, before a life-changing event brings him back to where he realizes he needs to be. It’s not a bad book, but nowhere near as good as Arrowsmith, because Cronin was more of a popular story-teller rather than the great writer that Lewis was.

The Adaptation:

Ah, yes, the life-changing event. That’s the doozy. See, much of the early part of the film is straight from the book. And I mean straight – most of the lines in the first twenty minutes are word for word exactly as they were on the page. And even a lot of the later parts come straight from the book, the dialogue exactly as Cronin had originally written it. And then we get that life-changing event – the death of the best friend – that pulls him out of the haze he has been in and points his life back in the right direction. Except that in the book, it is his best friend, Denny (played so well by Ralph Richardson) that helps point him in the right direction after his life-changing event: the death of his wife. Yes. A film that so closely follows the source material takes an incredible turn at the end, killing off a completely different major character to set the climax on its path.

The Credits:

Directed by King Vidor. Screen Play by Ian Dalrymple, Frank Wead, Elizabeth Hill. Additional Dialogue: Emlyn Williams. Based on the Novel “The Citadel” by A.J. Cronin.

The Film:

I have already reviewed this film once. This is what I said about it: “The acting isn’t bad and the writing isn’t bad. It’s just all kind of there.” But you’ll notice I didn’t say that the acting is good (Rains is good, Garfield is okay) or that the writing is good (it isn’t, particularly – it’s fairly standard).

The Source:

“Sister Act” by Fannie Hurst (1937)

First of all, no matter what you read, “Sister Act” is not a novel. It’s a short story that appeared in the pages of Hearst’s International-Cosmopolitan Magazine in March of 1937. It is also, surprisingly, really difficult to get hold of. Even the Hurst collection at Brandeis doesn’t seem to have a copy of it, at least according to the finding aid.

The Adaptation:

With the length of the kind of story that would have appeared in a single issue of a magazine, especially one that wasn’t strictly aimed towards fiction, it is unlikely that there is much more than a blueprint for what would become a feature-length film. I can’t know precisely, of course, and to be frank, I’m not really that bothered. The film is unmemorable, unless you count the fact that it was nominated for Best Picture instead of Curtiz’s Angels with Dirty Faces and for Best Director instead of Curtiz’s Adventures of Robin Hood. So, it’s memorable for being a ridiculous choice by the Oscars.

The Credits:

Directed by Michael Curtiz. Screen Play by Julius J. Epstein and Lenore Coffee. From the Cosmopolitan Magazine Story by Fannie Hurst.

Other Adaptations (in descending order of how good they are):

- Of Human Hearts – A solid Civil War story adapted from a short story. Not easy to find.

- Algiers – It’s the Pépé le Moko remake three years before the original would even hit the States. The original is considerably better.

- The Beachcomber – An enjoyable comedy with Laughton and Lanchester. Called Vessel of Wrath in the U.K., which is the name of the Maugham short story it’s based on.

- Jezebel – Adapted from the Owen Davis play (and intended for Bette Davis before Gone with the Wind was even written, so stop that rumor already). Good, but it’s the acting and directing that are strong here (well, the acting from the females) as opposed to the writing.

- Three Comrades – Based on the novel by Remarque, but probably more known for being one of Scott Fitzgerald’s few credited works in Hollywood.

- Young and Innocent – One of the later British Hitchcock films, good, but not good enough. Based on a novel by Josephine Tey.

- The Shopworn Angel – A charming film with Jimmy Stewart and Margaret Sullavan, from a Saturday Evening Post story that had already been filmed twice.

- Holiday – Though, this film with Hepburn and Grant, is the far more well-known version, the 1931 version had been nominated for Best Actress and Best Adaptation. I think this is a better film but still not a classic.

- Vivacious Lady – Jimmy Stewart is with Ginger Rogers this time, in a short story by I.A.R. Wylie, who also wrote the serial The Young in Heart was based on (see below).

- White Banners – Very hard to find. This is the film Fay Bainter was nominated for Best Actress for with her famous double nomination. It’s got an even better performance from Claude Rains. See it if you can, just for the acting.

- The Divorce of Lady X – Adapted from a short story, like all pre-Wuthering Heights films, this is Olivier before he really knew how to act on film.

- The Childhood of Maxim Gorky – The first of Mark Donskoy’s Gorky trilogy, adapted from the author’s memoirs.

- If I Were King – Preston Sturges did the script from a play, but it’s mediocre director Frank Lloyd who directed, so it’s never better than okay.

- Marie Antoinette – Stefan Zweig’s book gets turned into a showcase for Norma Shearer. She’s solid, but Robert Morley is better.

- The Young in Heart – Nominated for 3 Oscars but just about the least memorable Janet Gaynor film.

- Love Finds Andy Hardy – The fourth of like a zillion of these films, this one is key because it has Judy Garland and she’s adorable.

- The Buccaneer – Adapted from the novel Lafitte the Pirate, the 1958 version is actually a better film.

- A Slight Case of Murder – Edward G. Robinson stars in an adaptation of a Runyon play.

- The Amazing Dr. Clitterhouse – The same three stars as Key Largo (Bogie, Robinson, Trevor) and yet, barely above mediocre.

- The Sisters – Errol Flynn and Bette Davis aren’t as good as Flynn and de Havilland in this adaptation of a Myron Brinig novel.

- The Dybbuk – A Polish film, adapted from a play by Sholom Ansky.

- Mr. Moto Takes a Chance – The fourth Moto film.

- Mysterious Mr. Moto – The fifth Moto film, with a script by original Moto author John P. Marquand. Both films are okay.

- The Adventures of Tom Sawyer – Norman Taurog does Mark Twain. Very bottom level *** film.

- Sweethearts – Another MacDonald / Eddy musical, this one directed by Woody Van Dyke.

- Room Service – The first time the Marx Brothers star in an adapted script not originally meant for them. And it shows in the results, which are low-level **.5.

- Just Around the Corner – Again, a low level **.5, this one starring Shirley Temple in a short story adaptation.

- My Bill – Not the worst film of the year, but close. ** from John Farrow, adapted from the play Courage.

27 January, 2020 at 12:55 pm

I actually liked Four Daughters. It’s a rather inconsequential romantic drama that’s pleasant enough and harmless.

Vivacious Lady was a very entertaining romantic comedy and was consistently engaging for me. I thought James and Ginger had excellent chemistry and the main reason the film works well. You could quite easily see how George Stevens moved from this to The More the Merrier, another brilliant screwball comedy.