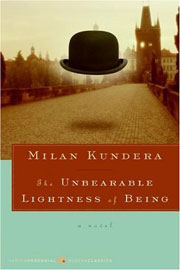

- The Unbearable Lightness of Being (Nesnesitelná lehkost bytí)

- Author: Milan Kundera (b. 1929)

- Rank: #76

- Publisher: Gallimard (France)

- Publisher (U.S.): Harper & Row

- Published: 1984

- Pages: 314 (Perennial Library)

- First Lines: “The idea of eternal return is a mysterious one, and Nietzsche has often perplexed other philosophers with it: to think that everything recurs as we once experienced it, and that the recurrence itself recurs ad infinitum! What does this mad myth signify?”

- Last Line: “The strains of the piano and violin rose up weakly from below.”

- ML Edition: none

- Film: 1988 (**** – #5 film of the year – dir. Philip Kaufman)

- Read: Summer, 1996

The Novel: I have never met someone who has read this novel and not loved it. I had one co-worker, at Borders, who recommended it to every single customer that he possibly could. People don’t love it for the plot. The plot can be explained simply enough. Tomas, a doctor in Prague, has a sexual relationship with Sabina. They both believe in the separation of sex and relationships. They fuck without connecting. Then Tomas meets a waitress named Tereza, who eventually follows him back to Prague. He lets her stay with him, then they marry. Then 1968 arrives with the Prague Spring and their lives are uprooted.

But the novel is so much more than that. It is a celebration of life itself. In the first sentence it brings up Nietzsche’s notion of eternal return and then posits that against the idea that there is but one life, one chance. “What then shall we choose? Weight or lightness?”

We are witness to the lightness that Tomas feels, only to be bound by the weight of his love for Tereza. Yet, Tereza has her own defenses against the world: “The camera served Tereza as both a mechanical eye through which to observe Tomas’s mistress and a veil by which to conceal her face from her.” But the lightness and meaning of life come under the shadow: “All previous crimes of the Russian empire had been committed under the cover of a discreet shadow.” Kundera, by this time, was living in France, having left Czechoslovakia in 1975 and never having been allowed back. His first novel, The Joke, about a joke in a postcard that gets a man crushed by the government, ended up with him being censored by the authorities in the year after the Prague Spring. The Unbearable Lightness of Being, written in 1982, was not published until 1984 and then it was published first in French, with an English translation getting released before it was ever released in Kundera’s native Czech (since the early 90’s, all of Kundera’s novels have been written in French). The novel provides yet another piece of literary evidence to the Prague Spring, adding literary weight to what Czech photographers and cameramen had already done: “preserve the face of violence for the distant future.”

With the Spring, the novel splits in two. Part of the novel follows Tomas and Tereza, first to Geneva, then back to Prague to witness the events of their country’s history. But it also follows Sabina as she precedes them to Geneva, yet stays true to her and Tomas’s philosophies of the lightness of being and of unattachment.

Kundera’s novels are unlike anyone else’s. They are modernist philosophical novels that give a view of the world, yet with a distinctly post-modern style that takes a step back and involves the very process of telling the story. Indeed, Kundera himself tells us “It would be senseless for the author to try to convince the reader that his characters once actually lived.” Kundera comes back around to points, steps away from his characters to observe what they are doing and why, lets us know the historical scope. His novels are something other than novels while still behaving like novels at the same time. So we can have a line like this: “Tereza’s dream reveals the true function of kitsch: kitsch is a folding screen set up to curtain off death.” But yet, we have the wonderful final section in which we feel the warmth and love of Tereza and Tomas. Perhaps this book, even more than Gatsby, would have been well-served through that final fateful line: “So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.”

note: all quotations are from the translation by Michael Henry Heim

The Film: It’s hard to imagine that Daniel Day-Lewis was so completely unknown back in 1988. There were certainly art film enthusiasts who knew who he was and after the double whammy in 1986 of A Room with a View and My Beautiful Laundrette, certainly film critics knew who he was. But to believe that he could perfectly encapsulate Tomas in Milan Kundera’s amazing novel? Who could have predicted that?

In fact, the major cast members: Day-Lewis, Juliette Binoche and Lena Olin, were all pretty much unknown at the time. Yet, this film so perfectly introduced all three of them to the international film scene. Here was Day-Lewis, the most talented film actor of his (and perhaps any) time. He is believable, both as an accomplished surgeon, and as the hedonistic man who is the opposite of kitsch and so beholden to sex. Then there is Binoche, so quietly beautiful, hurt by her lover, yet taken enough to follow him to Prague and to have him follow her away. Then there is Lena Olin, a year before her Oscar nomination as sex personified, here in a preview performance as sex personified, so perfectly positioned on the floor in that bowler (the hat, so vital to the book, present even on the cover, is also so vital to the film).

What is so impressive about this film is that it does something that is so rarely done in film. It combines the erotic with the philosophical without sacrificing either one. This is a serious film, one that has a serious philosophical view on life (which is actually expressed), with incredible cinematography, excellent direction and phenomonal acting from everyone involved. Yet, it is a seriously erotic film as well. There are amazing sex scenes between Day-Lewis and Olin and a photography session involving Binoche and Olin that would make anyone feel a bit steamy. In its lax attention to the growing amount of violence but complete hang-ups about sex, this is the kind of film that has been lost in American film. That it actually earned a Golden Globe nomination for Best Picture (Drama), yet managed to fall short at the Oscars to Working Girl is one of the few times that the Golden Globes has shown to have more depth and sophistication than Oscar voters.

Leave a comment